In the early 20th century, the city of Glasgow was a hotbed of political and social unrest, the result of years of conflict and a history of anti-war activism and rebellion among the working classes.

By the time the Armistice was signed, and thousands of demobbed soldiers poured into the city in search of work, the trades unions were ready to confront the bosses over working hours – and the resulting conflict landed the city on the brink of open rebellion for a few mad days in late January 1919, culminating in Bloody Friday, as the demobbed men fell in with the workers in a show of strength.

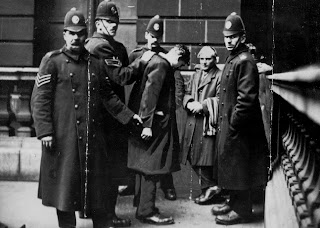

As the Red Flag flew in George Square, there was a sudden police baton charge, and a panicked Government sent in troops and tanks in a misguided effort to keep the peace, confining the local Glasgow militia to barracks lest they joined the strikers in sympathy. Newspaper headlines screamed of insurrection, while Ministers declared it was nothing less than a Bolshevik uprising.

It is only recently that scholars have reclaimed documents that tell of Red Clydeside, and of the dozens of mutinies that broke out all over Britain, Europe and North America in this troubled post-war period.

All of the above is a matter of record, and the latter chapters are based on events as they happened. I took a little artistic licence in that I condensed the strike into fewer days, but the running battles are based on eye witness accounts.

All of the above is a matter of record, and the latter chapters are based on events as they happened. I took a little artistic licence in that I condensed the strike into fewer days, but the running battles are based on eye witness accounts.As for the Bolshevik elements, there were strong links between Glasgow and Russia (pictured), and there are a number of scholarly works about ‘Red Clydeside’, the strike leaders and the beginnings of a class struggle.

If there weren’t any Bolshevik cells, then people were terrified that there might be, and the gist of the gun-running story is apparently true. Vera Radchenko may not have existed, but many key revolutionary figures in Russia and Germany, for example, were redoubtable females committed to the cause.

The book’s main characters are fiction, but a couple of real-life individuals found their way into the story: Davie Kirkwood, one of the more moderate strike leaders, and the Provost of Glasgow himself. Local history buffs might recognise the scene photographed by Alexandra took from City Chambers as the evocative shot often used to sum up that day, a sea of men in hats and young chaps hanging on to the lamp posts with the red flags billowing.

Some of the locations, such as the Aegean Trade Company, the baklava café and the derelict warehouse where the Bolsheviks run their operation, are make-believe. However, the docks as described are based on the original Clydeside in its heyday, bristling with cranes, ferries and tugboats, and an immense workforce.

Some of the locations, such as the Aegean Trade Company, the baklava café and the derelict warehouse where the Bolsheviks run their operation, are make-believe. However, the docks as described are based on the original Clydeside in its heyday, bristling with cranes, ferries and tugboats, and an immense workforce.

Will Fyffe’s famous ‘I belong to Glasgow’ simply had to make its way into the story (even though it only became popular in 1920). It seemed appropriate that the charismatic Finian O’Donnolly would recognise the potential of a throwaway line on a boozed up night out (Chapter 11). It seems Fyffe got the inspiration for the song from a drunk he met at Glasgow Central Station. The fellow was apparently ‘genial and demonstrative’ and ‘laying off about Karl Marx and John Barleycorn with equal enthusiasm'. Fyffe asked: ‘Do you belong to Glasgow?’ to which the man replied: ‘At the moment, at the moment, Glasgow belongs to me.’ As a result of this song, Will Fyffe became forever associated with Glasgow, even though he was born in Dundee.

St Peter’s is a fictional university with traits that might be recognisable to anyone who has travelled north of Edinburgh, but sadly, there was no Dr Nairn, or even a Spanish entremesista called Ramón de Vela.

The subversive qualities of 17th-century interludes is now a respectable topic, and I recall with affection a particular visiting American scholar from Buffalo, of all places, who set me on the right track when I was studying an authentic interlude writer, Luis Quiñones de Benavente, whose short plays are jam-packed with political and religious satire (when you know where to look). A contemporary of Lope de Vega, he has slipped from the history books.

The subversive qualities of 17th-century interludes is now a respectable topic, and I recall with affection a particular visiting American scholar from Buffalo, of all places, who set me on the right track when I was studying an authentic interlude writer, Luis Quiñones de Benavente, whose short plays are jam-packed with political and religious satire (when you know where to look). A contemporary of Lope de Vega, he has slipped from the history books.I hope those more familiar with Glasgow’s history will forgive a rethinking of the end of the infamous strike. It is a shocking liberty, especially given that the author was born in Edinburgh, but the story of the so-called ‘Revolution that never was’, is a fascinating story that deserves to be retold.

Sources:

Non-fiction

Red Scotland!: The Rise and Fall of the Radical Left, c1872 to 1932, William Kenefick (Edinburgh University Press 2007)

When the Clyde Ran Red, Maggie Craig (Mainstream 2011)

Revolutionary Women in Russia 1870-1917: A Study in Collective Biography, Anna Hillyar, Jane McDermid (Manchester University Press, 1999)

The Mediterranean, Ferdinand Braudel (Collins, 1978)

Online

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RUSkrupskaya.htm

http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/sr226/rosenberg.htm

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Major+changes+in+%22minor%22+theater%3A+Luis+Quinones+de+Benavente%27s...-a0194333470

http://libcom.org/library/mutinies-dave-lamb-solidarity

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers/alevelstudies/1920-industrial-relations.htm

http://thegreatunrest.net/2010/09/03/forgotten-history-the-belfast-engineering-strike-1919/

http://www.gtj.org.uk/en/small/item/GTJ69242/

http://libcom.org/history/1911-liverpool-general-transport-strike

http://liverpoolcitypolice.co.uk/#/police-strike-1919/4552230277

http://libcom.org/history/1919-the-southampton-mutiny

http://gdl.cdlr.strath.ac.uk/redclyde/index.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/history/modern_scotland/glasgow_rent_strikes/

http://www.gcu.ac.uk/radicalglasgow/chapters/rebellion.html

http://libcom.org/history/articles/red-clydeside

http://urbanglasgow.co.uk/archive/-bloody-friday-glasgow-s-general-strike-of-1919.__o_t__t_792.html

http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=15&t=7510

http://libcom.org/history/1919-the-forty-hours-strike

http://glasgowguardian.co.uk/uncategorized/the-battle-of-george-square/

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/demobilisation.htm

http://www.glasgowhistory.com/sailing-down-the-clyde-%E2%80%9Cdoon-the-watter%E2%80%9D.html